Confessions of an Angry Autist

Below is an article by Ari Winters originally published on May 14, 2023 on Medium. It is reprinted here with their permission.

Ari Winters is a professional facilitator and creator of The Relating Languages. Growing up, they were drawn to the complexities of human interaction, acting as a bridge between different social circles and communities. This sparked their fascination with facilitating discussions and fostering connections between people from diverse backgrounds. They have worked with organizations such as Google, Dell, Mindvalley, Rebel Wisdom, Kellogg, and the National Weather Service, teaching communication and leadership skills. Winters participated in an interview for Learn from Autistic People about socialization and the Relating Languages Program that will post next week.

My name is Ari Winters, and I am autistic.

I discovered this recently. I discovered it after ten years of teaching people how to mask.

At the time, I thought I was teaching communication skills. I taught how to be more empathetic, more aware. How to be curious under pressure. How to “read a room”, recognize when you’re speaking too much, and set contexts that allow your full self to emerge.

The problem is, in all that time, I wasn’t allowing my full self out.

- I was overwhelmed in groups, but I forced myself to facilitate them.

- I hated eye contact, but I forced myself to look.

- I constantly misinterpreted social dynamics, and then judged myself for the feedback I got.

The more I taught, the more I learned. But the more I learned, the more I felt overwhelmed by my own expectations. Why couldn’t I always use the skills I taught my students? Why did I shut down when things got intense? Why did I always miss or misinterpret someone’s needs?

Why did it feel so hard to…everything?

Sometimes, I would meet another person like me. I didn’t have words for why they were My Kind of Furby. I just knew that their brain worked like mine.

- They categorized everything.

- They analyzed all their feelings.

- They found people overwhelming, but they were still trying to interact.

- They created heuristics for behavior and followed them, instead of just “feeling their way through” like other people apparently do.

These people became my friends. One of them, Ari, became my teammate.

My neuro-bland friends often found his lack of facial expressions and social considerations offputting, but I didn’t care. He understood his motivations. He lived his values. What was not to love?

Then, one day, he mentioned that I might be autistic too.

My first response was anger.

How dare you say I’m autistic?

Haven’t I spent my entire life studying and practicing connection?

It doesn’t matter if I was autistic. I’m not anymore.

Then I thought about it. And I realized he was right.

It was one of the saddest realizations of my life. Everything I’d put in that category of “need to work on this” and “to fix” all of a sudden had a definition.

My superpowers did too: my ability to make maps and concepts, to break down intuitive communication into a way my brain (and therefore others’) could understand.

But I didn’t feel that yet. I just felt pain — as if someone had told me, “you have an incurable disease, and all of the symptoms make sense.”

I had spent ten years studying connection so I could learn to mask and be “normal”. Now, it seemed, I never would be.

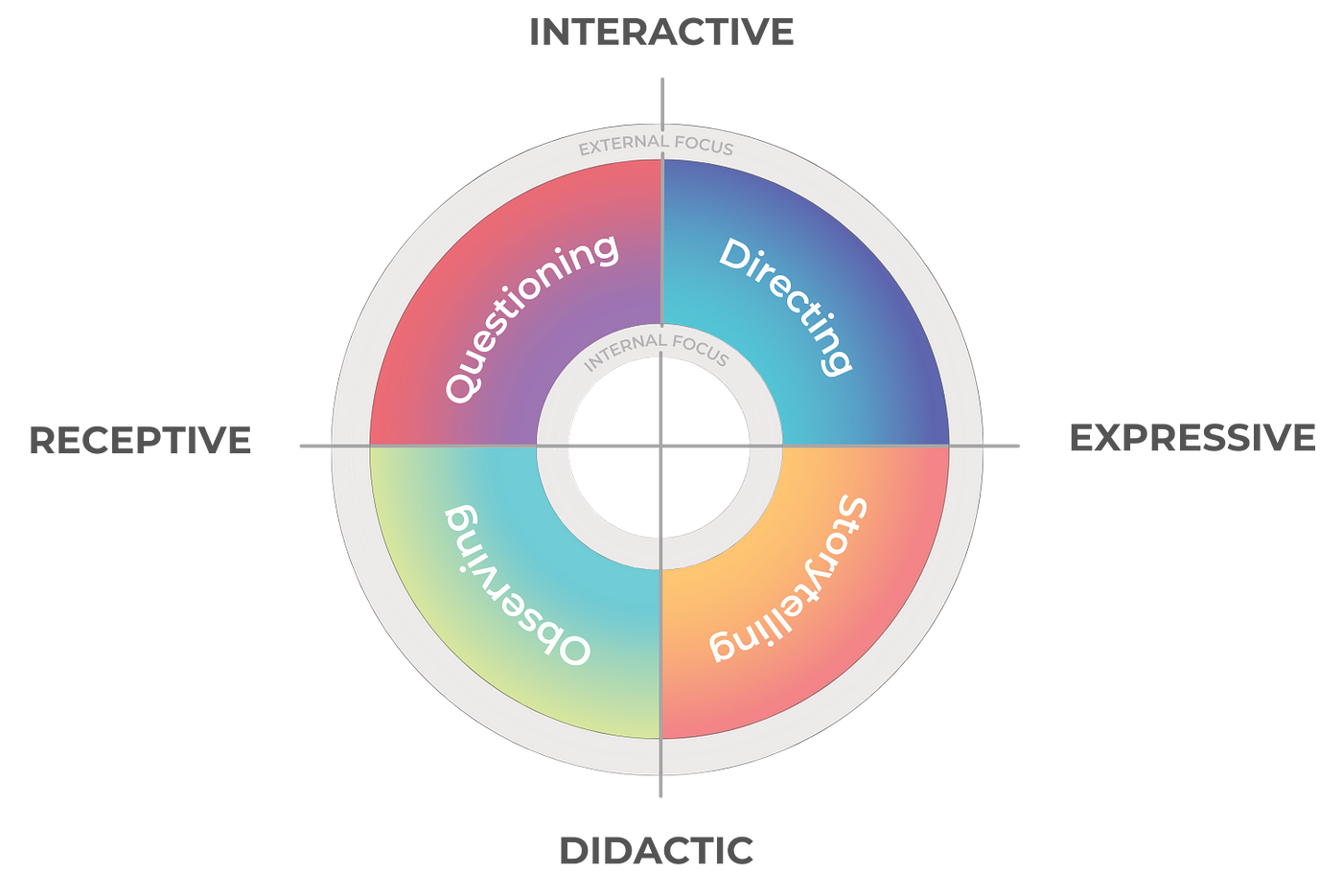

I’ve been working on a new project with my team, and all of a sudden, my interest in it made sense too. We are working to categorize communication into “Relating Languages”, codices that can explain why people continuously misunderstand each other. Our theory is that it isn’t always the content of the communication that causes conflict. It’s howthat content is said, combined with our expectations of how it should be said.

I love this theory, because it tells me that I am Not Wrong.

Instead of “I talk too much”, it says, “Your most common language is being a Storyteller. You’re motivated by wanting to entertain, wanting to fill space, wanting to get your point across. You expect people to bring their voice forward and interrupt if they have something to say.

“You’re not an Observer, tracking social dynamics. You’re not always able to Direct towards what you need. You only Question when you feel safe.

And that’s okay.

There is a place for you.”

You can find your own Relating Language, or learn more about the system, using the short test at https://www.relatinglanguages.com/.

I am Ari Winters, and I am autistic.

I’m not happy about it. Maybe someday I will be, once I get over the grief and anger of finding out.

But I’m going to tell my story.

I’m going to help others — autistic, neuro-spicy, “normal”, or however you identify — understand their own languages and ways of being.

Because, to me, that’s what embracing autism means:

Knowing you’re weird.

And doing it anyways.

Yours,

Ari

Want to learn more about Relating Languages? Visit https://www.relatinglanguages.com/neurospicy

…