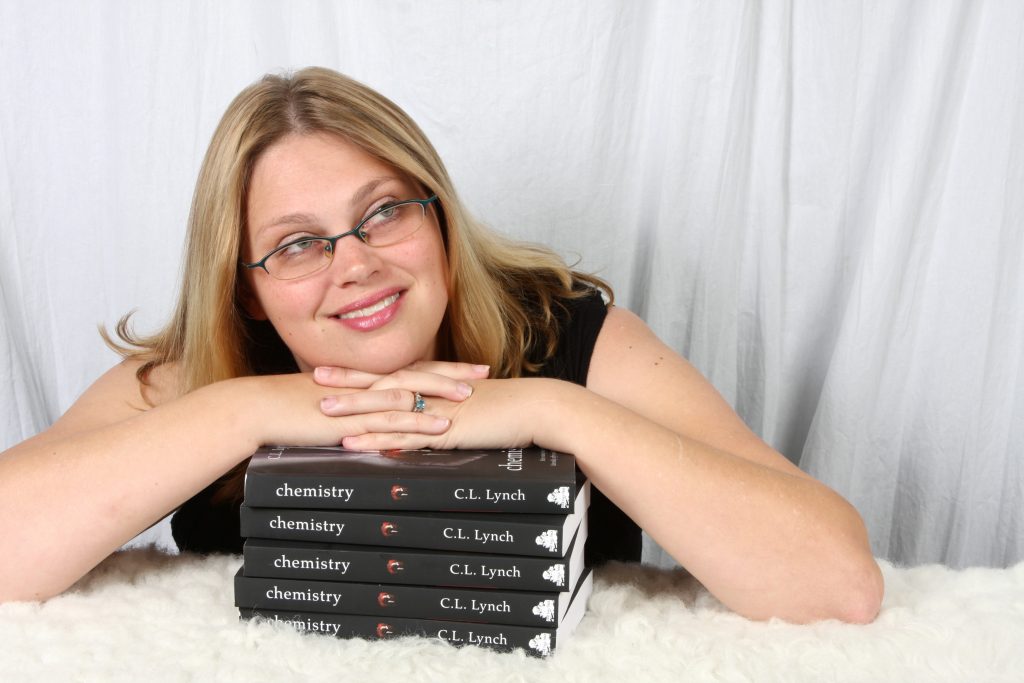

This is the second part of a two-part interview with Canadian novelist and autistic advocate C. L. Lynch. Last week she shared her personal diagnosis story and explained why she advocates for a complete overhaul in autism severity labeling. She offered an excellent perspective on language surrounding autism and how we can better understand and support autistic individuals through the words we use. This week she discussed ableism in literature and how parents can raise their children without ableist attitudes and advocate for positive autistic identities.

In your article about the ableism of Stella, the main character in your Twilight antithesis novel, Chemistry, you mention that you intentionally wrote her character to be ableist and expected to defend your intentionality and explain the future of her character development. Were you surprised at the lack of criticism in this regard? Do you think this is due to a general ignorance of the pervasiveness of ableism, a sincere trust in your character development, or something else?

I was really surprised, but I shouldn’t have been.

People mostly love Stella, though the occasional person complains about how aggressive and petulant she can be. But not a single review, rave or rant, decried her ableism.

Ableism will be the last “ism” that we eradicate, if we ever do at all. The belief that illness makes us worth less, that disability lessens our value – especially cognitive disability – is so ingrained that I have seen small children express it. We insult each other with words like “stupid” or “lame” and those get less reaction than even the correct medical names of certain body parts, or the words for medical descriptors like “autistic.” No one blinks when Stella calls someone “crazier than a syphilitic republican” or agonizes over whether dating the special-needs guy with cognitive problems (aka “a zombie”) and special diet requirements (brains) will affect her social life.

Ableism is deeply ingrained into story telling and literature, and I think the subversion of this is one of the most important things authors can do to change the narrative both in fiction and in the real world.

I mentioned Canadian author Jean Little in the first part of this interview, but I’m going to do it again. Little often writes books about characters with disabilities, yet she always makes the story about something other than the disability. No one is ever cured in her books.

She wrote her first story, “Mine for Keeps,” about a girl with cerebral palsy, because when she was a teacher of disabled kids, her students complained about how The Secret Garden ends with Colin walking toward his father, and how in Heidi, the book ends with Clara showing her father that she can walk and is well now.

The erasure of disability as a “happy ending” is a very common story trope. And the ending of disability through suicide is another one – in stories like Me Before You or Million Dollar Baby.

But imagine how it feels to know you have an incurable disability and to be told that you can’t have a happy ending, and that death may be preferable.

Little’s students knew THEY weren’t going to end up walking some day, and they wanted to know why they couldn’t have happy endings without the use of their legs. So their teacher wrote them one. And another. And another. Little’s books cover everything from deafness to cancer and no one is cured. But all of her books have happy endings.

THAT is what the social model of disability and its brain child, neurodiversity, is all about. People want to portray it as a heartless and misguided lack of compassion for people like Ido Kedar who suffer badly from their condition.

It isn’t.

It’s about believing you can have happy endings even without a cure.

Like Jean Little, I wanted to write a story where a character learns that sometimes disability and neurodiversity is not only something worth overlooking in order to find love, but IMPORTANT to finding love. Over the course of the series Stella learns to love her zombie suitor not despite but BECAUSE of his differences, which for better or worse make him who he is.

I hope that some of my readers see that, and learn along with Stella.

What are some basic ways you are raising your children to avoid the ableism that is so pervasive in the world?

“Everybody is different.” We’ve been saying it as a mantra, and my eight- year-old son now does too. When he eats broccoli and his friend says “Ew, that’s gross!” my son shrugs and says, “You don’t like it, but I do. Everybody is different.” And when his little sister rebelled at being called weird, he said, “What’s wrong with being weird? Everyone has something weird about them because everybody is different.”

People send a lot of conflicting messages at children. Kids are constantly told to be themselves, to celebrate what makes them unique, but if they take that a little too much to heart, they get told, “No, not like that.”

My husband and I try not to do that. We try to look for things like goodness, kindness, and empathy, and only reign our kids in when what they are doing infringes on the rights of others.

We haven’t spent much time specifically discussing ableism. But when my kids use words, I make sure they know what they mean. When my son called someone “dumb,” I told him that “dumb” means “not speaking” and asked him why he thinks that should be an insult.

Now if someone calls him dumb, he educates them.

When he complained about a friend of his who has oppositional defiant disorder, I reminded him of how he used to wet the bed until he was seven years old. “Different parts of your body grow at different rates,” I told him. “Your body grew faster than your bladder, but your bladder caught up eventually. The part of your friend’s brain that handles feelings is not growing as fast as the rest of him, but it will catch up too.”

By remembering our own struggles, I hope we can learn to accept the struggles of others. Bit by bit we can make the world a more inclusive and accepting place if we just understand that everyone has struggles and that having struggles does not lessen our value as people.

What mistakes do you see neurotypical autism advocates make?

I see them assume that autistic people want the same things non-autistic people want. I see them break their heart over the inability to talk as if it is the worst possible fate. I see them point to flapping hands as a distressing indicator of difference. Neurotypical people seem very distressed by difference… at least in people. Meanwhile autistic folk tend to be much more distressed by difference of routine, difference of location, difference of food availability. Difference between one human and another? Well that seems pretty natural to us and not necessarily horrifying or worthy of outcry.

Like, why does it matter if I communicate by voice while another person communicates by tablet? Why is the AAC user seen as suffering so much more than I am?

Neurotypical people assume that autistic people want to stop being so autistic. They assume that stims are distressing, because they are odd

looking and therefore MUST be distressing. They assume that we want to “be normal.”

But really what most autistic people seem to want is just… happiness.

And happiness for us may not look the same as it does for a neurotypical person.

Sure, someone with neuromotor problems will want to improve their ability to move their body, and someone with anxiety will want to decrease their anxiety. But not everything about autism needs to be changed to be happy.

In fact, many aspects of autism cause happiness. I’m sad for my husband, who can’t experience the bliss of rubbing my stim blanket. It does nothing for him. I pity neurotypicals when I read articles on how to achieve the elusive “flow state” which is so very zen, because that is a routine part of autistic existence. Why do you think we get so annoyed when you interrupt us from a stim or a special interest?

Autistic people learn very early that the people around them think differently, like different things, feel different ways about life than we do. But neurotypicals take certain base assumptions for granted, and it never occurs to them to think that maybe we don’t feel the same way.

Most autism “therapies” are based on neurotypical goals – getting the child to hit neurotypical milestones or learn to do neurotypical things. The idea is that normalcy must be happiness, and it never seems to occur to anyone that this may not be the case. And if we argue that, if we try to explain that normalcy and happiness are not always the same thing, we get accused of not caring about other autistic people who are suffering. We don’t want anyone to suffer. We just don’t want you to assume that being different is the same as being unhappy.

Most autistic people seem to want comfort, love, predictability, stability, acceptance, the ability to express themselves, and the freedom to pursue their own interests. Autism only really causes us suffering when it interferes with those things, and when it does, it is often the reaction of neurotypical people that really causes the most suffering. An inability to speak aloud is inconvenient, but if we are given free and easy access to AAC, we can still get our thoughts across. But deny us AAC, and autistic people spend years unable to express themselves, listening to conversations that exclude them, listening to people talk about them as if they aren’t even in the room. That is suffering, but is it really autism’s fault at that point? Or the fault of the neurotypical reaction to it?

The other, and possible biggest, mistake neurotypical people make is assuming that the outside reflects the inside. If an autistic person does not appear to understand, they are assumed not to understand. Big, big mistake. The pervasive belief that ‘severely autistic’ people are intellectually disabled and oblivious to their surroundings – incapable and uninterested in communicating – is incredibly harmful to all autistic people.

It’s harmful to those “severely autistic” people because they suffer with being treated like small children well into adulthood, hearing them spoken of behind their back right in front of them, and are denied the ability to communicate. But it’s also harmful to people like me, who are assumed to be doing just fine because we LOOK like we are doing just fine.

I’m really not doing just fine.

What advice do you have for parents who are trying to raise their children with a positive autistic identity?

I would avoid talking about “deficits” and instead talk about their needs and likes. For example, they don’t struggle with metaphorical language – they like things to be stated plainly and literally. They don’t struggle with noisy locations – they like things to be quiet and calm. They don’t fail to make eye contact, they like to look away when listening.

I would talk a lot about how they see the world and how others see the world. Let them know that some people feel like you aren’t listening if you don’t look at them, and tell them that if someone says “are you listening to me?” or repeats their name, to look them in the eyes for a second or two and say, “I’m listening.” But don’t tell them to do it because it’s right and they are somehow wrong. Tell them to do it because it makes the other person more comfortable.

Autistic people are BIG on comfort – we want it for ourselves and we understand why others want it too. When we can, we will try to make others comfortable even if it means temporarily making ourselves uncomfortable.

I would avoid suggesting that they are loved “despite” their autism and instead because of it. Tell them you’re proud to have a kid who communicates by tablet instead of by voice. Tell them you’re delighted to have a kid who learns best when jumping up and down. It may not be true – at least not all the time – but it’s so important for a kid to know that they are loved for everything about them, not despite the things that make them different.

I grew up with quite a positive self-image, because the asperger’s type of autism is so common in my mother’s family that I didn’t strike her as weird at all. It wasn’t until I was much older that I learned how weird of a kid I had been. I told my mother how amazed my psychologist had been by my first novel which I wrote when I was ten. The psychologist couldn’t believe I had written and illustrated a ten-chapter novel, complete with dialogue, description, and a coherent plot, in grade 4.

“Why? Is that not normal?” my mother said in response.

Well, in our house it was.

So let your kid feel normal, not by teaching them to act more “normal,” but by thinking of them as normal just the way they are.

——————————————————————————————————————–

You can follow C. L. Lynch’s work at her website http://cllynch.com/.