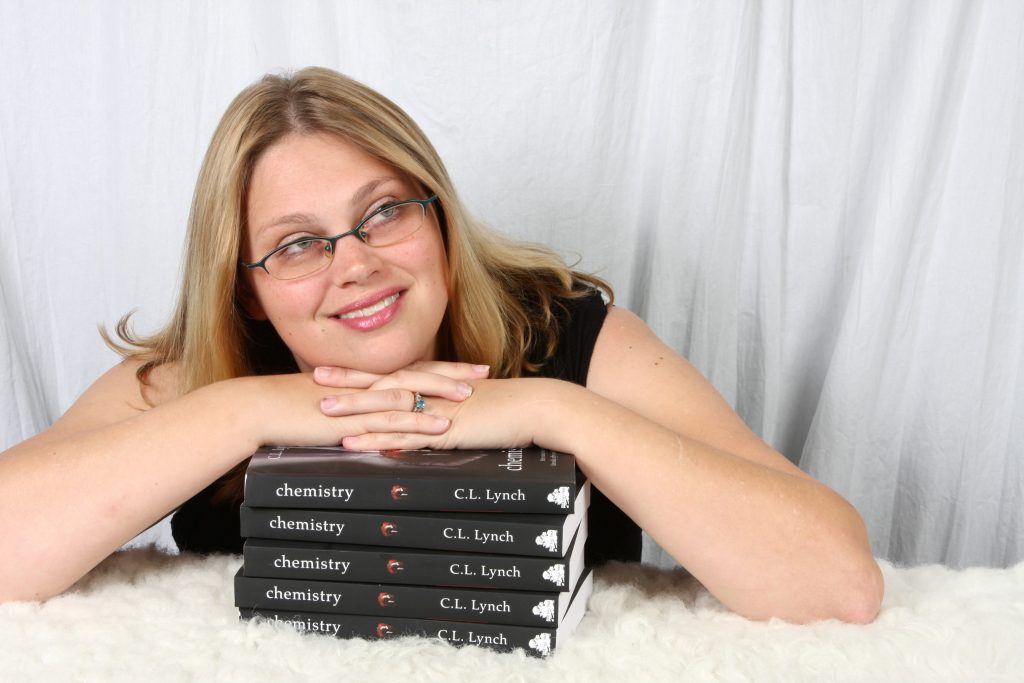

C. L. Lynch is a novelist and autistic advocate from Vancouver. Her breakout novel Chemistry came about from the intention to write a book that was “the exact opposite of Twilight.” She also writes about her recent autism diagnosis and advocates for improved autism awareness and understanding. This is the first part of a two-part interview with C. L. Lynch in which she discusses her personal diagnosis story, how her diagnosis changed her marriage, and why she advocates for a complete overhaul in autism severity labeling (beyond merely avoiding “high” and “low” functioning labels).

How recently did you receive your autism diagnosis? Can you give some specific examples of how your life is different today because you are aware you are autistic?

I was officially diagnosed in 2018 by a psychologist who specializes in autism and developmental disabilities and who heads the Autism/LD department of her university. I self-diagnosed in 2017 after reading an article about how autism presents in women.

It’s funny, because I’ve always had a “special interest” in autism. I was always checking books on autism out of the library, I followed people like Ido Kedar and Carly Fleischmann online, and only the week before I read that fateful article, I had donated to the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. I already knew that Autism Speaks was bad and that you shoud say “autistic” not “person with autism,” and yet I didn’t think I was autistic. I used to joke that my mother’s whole side of the family was on the edge of the spectrum and my husband used to tell funny stories about how literal and anxious that side of my family is.

But we never dreamed that I was autistic.

When I read the article about how autistic women tend to have fewer difficulties with communication and more difficulties with executive function, something kind of RANG in me like a gong. I re-read the article several times and then asked my husband to read it.

My husband was cautiously supportive, in a “I don’t think you’re right, but I’m not going to invalidate your feelings by saying so” kind of a way.

Then I sent him some links describing typical “aspergers” traits and some links to descriptions of autistic women.

Within 24 hours, he was more convinced than I was. He kept showing me things he had found online.

“That’s YOU,” he said. “YOU’RE AUTISTIC.”

It changed our relationship dramatically. While we’ve always been close, when we fought, it was often over something I said that he totally misinterpreted. We’d have a long drawn out argument where I kept trying to make him see what I had really meant while he kept trying to make me see how hurtful I had been. We never really could understand the other person’s point of view and these arguments would sometimes fizzle out into long but silent resentments.

The self-diagnosis of autism stopped that in a heartbeat. My husband was gob-smacked as he reviewed our former arguments in his head. “You… really didn’t mean those things the way they sounded…. you meant them literally,” he said.

“I’ve been saying that for YEARS,” I said.

‘But now I BELIEVE you!” he said.

It’s not that he thought I was a liar. It’s just that it had never entered into his allistic head that I could POSSIBLY have meant such obviously hurtful things totally literally. I would have to be totally blind to subtext.

…Which, as it turns out… I am.

There’s a double-edge to an autism diagnosis when you’re in your thirties. One the one side, all of those slurs you’ve been slinging at yourself all your life – oblivious, self-absorbed, socially awkward, introverted, lazy, sensitive, high maintenance, obsessive, babyish… those all dissolve and just become one thing – AUTISTIC.

It’s hard to see “autistic” as an insult when you’re replacing all of those other mean labels with this one medical diagnosis instead. It feels like… an explanation.

But on the other hand, when you haven’t grown up with that label, when you’ve thought that everyone else had it just as hard but were handling it better than you, when you think that your experience is “normal”and that you, while maybe a bit babyish and lazy and awkward and introverted and anxious etc., etc., are also “normal”… it’s sobering to look at a piece of paper that says you are not.”

The hardest part for me was accepting that I really am missing a kind of social radar that other people have. It reminds me of a children’s book by the blind Canadian author Jean Little, called “From Anna”. The main character, a little girl named Anna, is nicknamed “awkward Anna” by her siblings. She’s clumsy. She can’t read, so she’s considered stupid by her teachers. She can’t sew. Everyone is always frustrated with her… until she emigrates to Canada and the doctor there discovers that she’s legally blind.

If you grow up assuming that everyone else sees the same things you do, it can be dismaying to learn that you are actually missing a lot of things that other people can see.

Getting my autism diagnosis was like Anna learning that she was practically blind.

You see, the psychologist gave me several written tests. In one of them, I had to read stilted dialogue exchanges between fictional characters and then mark any sentences that might make other people in the room uncomfortable. I breezed through it! It was easy.

In one exchange someone comes into a store, exchanges pleasantries with the clerk, and asks where they can find such and such. Then I’m asked if anything was said that could make someone uncomfortable. Nope!

Next – a guy says something snide about a woman at a party only to learn that she is the wife of the person he is talking to. Could that upset someone? Yep! Easy peasy.

I mean, I’m an award-winning author! I am KNOWN for my witty dialogue. Just look at my reviews – my dialogue and characterization are my biggest strengths as an author. Of course I could read dialogue and identify what was good and what was bad.

I was actually worried that this test would exempt me from being autistic – that it would make me look more savvy than I really am. Social interactions on paper are one thing. Real-time conversation is another.

Well… it turns out that I flunked that test.

Badly.

According to my report, I correctly identified less than half of the “blatant” social faux pas and zero – ZERO – of the subtle ones.

That is sobering, when you genuinely think you aren’t THAT autistic – that you do have autism, but are some kind of autistic savant when it comes to social skills and aren’t really affected in the pragmatic language category at all.

It turns out I’m actually quite disabled in that category, and I had no clue. I can write it… but I can’t read it, apparently.

That is sobering and humbling news.

But that drop in confidence is totally worth the positives that come from knowing why I am the way I am, and from my husband understanding it too.

In what ways is autism disabling to you? How do you self-advocate?

One of the hardest things to come to terms with when you are a highly intelligent person with autism is the fact that however smart you are, you do have a neurodevelopmental delay.

That delay manifests differently in different people – some people never gain control over their body movements, while others never figure out sarcasm. For me it came mostly in functional skills.

One is that I never figured out how to organize. I LOVE organization, I crave organization, I have been trying to organize things my whole life… but it just never came.

What this means is that I am constantly losing my things and storming around the house in a rage because I can’t find the thing I never put away.

It means that I need a place for everything and everything in its place, but I don’t know where that place is, and I need someone else to make sure the things I leave lying around end up there so I can find them again.

Basically I need my house to magically reset itself each night.

Another delay comes from my self image. In many ways I still see myself as a child. My twelve-year-old self still feels like “me” – when I look in the mirror and see a thirty seven year old, I don’t understand where I went. My clothing preferences are childlike, I still love my stuffed animals and talk about them like they are real people, and I often find myself sighing wishfully over clothes I see in the kids section and then reject everything I find in the adult plus size department. I own a unicorn onesie with a tail and a hood and these are some of my favourite pyjamas, even though I’m a grown-ass woman.

And I AM a grown woman. I have a university degree, a husband, a career, and two children.

Do not mistake “childlike” for “childish.” Emotionally, I’m a mature adult. But certain aspects of my sense of self are still locked in childhood, and I don’t think that will ever change.

That’s not disabling, though, just quirky.

The truly disabling aspect of my autism is my inability to, like… DO things.

It turns out that I really suck at doing things.

It never came up until I hit adulthood. School is mostly just sitting there and passively absorbing information. I can do that NO problem. Go to class, absorb info. Go to class, receive test, excrete info. NO PROBLEMO. I can do that ALL DAY.

School is just inhaling and exhaling information. I thrived in that atmosphere.

But once you leave school, people want you to work, and working is MUCH more complicated. You have to move your body around and complete MANUAL TASKS. You have to do it without explicit instruction, just KNOWING what should be done and then just, like… doing it.

You have to navigate complex social interactions on the phone or with clients or with bosses or with coworkers. You don’t just sit and listen to what people tell you – you’re expected to be PROACTIVE and DYNAMIC and SHOW TEAMWORK and LOOK BUSY, and, quite honestly, I’m total garbage at doing that stuff.

I don’t mean that I did my job poorly. I did my job to the best of my ability, and often that was as good or better than what other people could do. But it was hard. It wore me out, and it wore me down.

My mental health broke in 2009. It improved when I went on maternity leave for a year and didn’t have to deal with expectations from people outside the home. Sometimes weeks went by when I barely left the house and saw no one except my baby and my husband. I was in heaven. But then I had to go back to work again, and the anxiety came flooding back.

Then my husband became ill, and I lost my caregiver.

Before that, my husband washed the dishes, cooked, managed the money… basically took care of the household.

At that time we didn’t know he was my caregiver. I just thought he was awesome and he liked being awesome.

But over the years we have discovered that I CAN’T wash the dishes and cook and manage the money.

I am a specialist – If you think of attention as being a light, most people are lamps, or maybe flashlights… while I am a laser. My thoughts are incisive, sharp, and specific. I can carve my way through virtually any intellectual task with ease. But ask me to remember the thirty or so things I need to remember in order to prepare myself and my kids for the day? Nope. Can’t do it.

I can’t keep up with manual tasks, with interacting with the outside world.

The world in my head feels just as real and much easier to interact with than the meat-space of reality. That’s a big problem when the rest of the world wants you to treat it like it exists.

Your article explaining how many people misunderstand or misrepresent the autism spectrum does an excellent job outlining seven different skill sets and behaviors that make up the “spectrum.” Should society be avoiding terms like “more severely affected” to describe how someone presents? Could “severely affected” refer to difficulties with many or all of the seven skill/behavior categories you’ve broken down as making up the autism spectrum? Or should we ideally only be mentioning these specific subcategories of skills when describing someone on the spectrum?

I think that breaking down an autistic person’s individual needs makes MUCH more sense than trying to describe the “severity’ of their autism. There are many different flavours of autism, and some are much more visibly disabling than others. The most obvious example are the people who are often called “severe” autistics – the people who cannot control their muscle movements and are therefore seen (even by their own parents and therapists) as being oblivious and intellectually disabled. Even the lucky ones who are given access to letter boards and OT to help them gain control of their muscles still often require 1:1 care. There is no question that their autism affects both them and those around them severely, so I can understand why the label is used.

But really, it isn’t that their autism is more severe. It’s that they have motor control issues – called “apraxia” – that I do not have. But if you ask any autism specialist if autism is, at heart, a motor control problem, they will tell you “no.” Maybe they’re wrong – certainly all autistic people have strong feelings about the world around them and how they interact with it – but for now, apraxia is considered a side-order to the main dish that is autism.

So if autism isn’t a motor control problem, then why do we call autistic people with motor control problems “severe” autistics? Shouldn’t they be autistic people with motor control problems? Or shouldn’t they have “Apraxic autism”?

Ido Kedar has even proposed something like this – he says his condition is better described as “severe apraxia” than “severe autism.” He has been quite vocal about insisting that what he has is NOT a “severe” form of Asperger’s. His condition affects him severely, but that doesn’t mean that mine doesn’t also. Our conditions affect us totally and completely differently.

Does that mean that I can’t understand what he is going through?

No. We both stim. We both need prompting to interact with meat-space. We both find it hard to come out of ourselves and interact with the world. But those difficulties manifest quite differently. I can move and speak and interact easier than he can. But he can read people better than I can. He’d probably ace that damn social situations dialogue test I did.

I think it isn’t helpful to describe someone’s autism as “mild” or “severe.” Most autism professionals agree. The APA tried to fix this by rating autism instead by the level of support required. I would be “level 1” – I can live a close to normal life with the help of some support, whereas someone like Ido Kedar cannot, even with lots of support.

But even this is not helpful because I and other level 1 people might still be very different.

It just makes more sense to talk about what particular struggles the autistic person has and not try to compare us as being better or worse off than someone else who also has autism.

Further Reading

“‘It’s a Spectrum’ Doesn’t Mean What You Think” by C. L. Lynch

You can follow C. L. Lynch’s work at her website http://cllynch.com/.

Actually Autistic Blogs List

Actually Autistic Blogs List