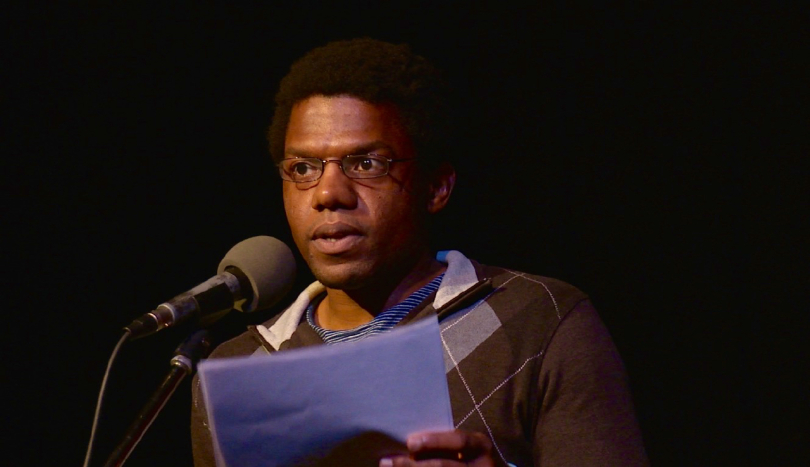

Bernard Grant’s writing has appeared in Crab Orchard Review, New Delta Review, The South Carolina Review, Third Coast, and Craft, among other online and print publications. Bernard serves as an Associate Fiction Editor of Tahoma Literary Review and holds an MFA from The Rainier Writing Workshop at Pacific Lutheran University where they were awarded the Carol Houck Smith Graduate Scholarship. They have also received scholarships to The Anderson Center, Sundress Academy for the Arts, and Fishtrap: Writing and the West, as well as fellowships from Vermont Studio Center, Jack Straw Cultural Center, Mineral School, and The University of Cincinnati, where they are a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature and Creative Writing, and are at work on a novel-in-stories that focuses on a mixed-raced family and features autistic characters. Bernard is also working on essays on autism and American racism, which they plan to collect and title Unmasking. This week Bernard discussed his life as an Autistic author and ways society can work towards autism acceptance.

When/how did you first become aware of your Autistic identity?

I discovered my autism in 2012, when I was twenty-six, and began working as a caregiver, working with several autistic adults, whom my coworkers were quick to other.

I hadn’t yet understood anything about neurodivergence or neurotypicalism, had yet to understand that I understood my clients’ behaviors because I was on their wavelength, a wavelength separate from my mostly-neurotypical coworkers.

I understood autism only in the misinformative way the company taught its employees to understand autism. I, therefore, denied my autism for several years, and avoidance resulted in autistic burnout.

I didn’t accept my autism until last winter, when the pandemic began, and I began to teach from home. Quarantine, what many referred to as isolation, I saw as an extended allowance of solitude.

At the start of the pandemic, I watched Hannah Gadsby’s stand-up special Douglas, which is mostly about (Gadsby’s) autism.

I also read A Very Late Diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome by Philip Wylie, an autist who stresses how vital it is for autists to find and accept ourselves, and while he gives tips for diagnosis, Wylie stresses that it is not necessary for an autistic adult to seek a diagnosis, as the resources for adults are overpriced. He also offers tips for self-identification.

Wylie uses the term “self-identification” rather than “self-diagnosis.” I like that term, “self-identification,” because I see autism as who I am rather than something I have.

I don’t need a diagnosis. A diagnosis is a professional opinion, and many of these professionals are neurotypicals, and many neurotypicals, including medical professionals, see autism as a problem. Autism was only a problem when I tried to avoid it.

Tell me about how you were first drawn to writing and what your writing schedule/life is like now.

I discovered writing as an undergraduate. At the time, my focus was film studies, though I wasn’t interested in filmmaking, as I’m a technophobe, and stuck to film theory.

A professor I’d been studying with suggested I take the second sequence of her film studies class, which would require me to shift my focus from thinking and writing about films to thinking about and writing screenplays, and as this was an adaptation course, I was required to writing a short story, then to adapt that story into a short screenplay.

My writing was a mess, but that class taught me that I enjoy writing creatively, though I don’t like to write screenplays. I prefer books to films, but one thing I love about films, perhaps because my autistic mind focuses on details, is that they allow me to read, to study language, via close captions, focusing on individual sentences rather than paragraphs.

My writing life is built into my routines, so I write during the week, though I occasionally write on Sundays. Saturdays I can’t allow myself to work, a rule I can never seem to break.

In your opinion, where can autism advocacy efforts improve? In other words, what do you see as the most effective, efficient, or important advocacy strategies to promote acceptance and improved quality of living for Autistic individuals?

Society needs to normalize autism, which means society should learn about and accept autists, and neurodivergency as a whole, as autism is a healthy variation of the human experience.

I’ve heard of companies in the UK that have autism hour, where they dim lights and turn off music in order to decrease sensory stimuli, as autists are sensitive to sensory information, which we’re continuously processing. Society should do more of these kinds of things.

I want to live in a society where, if I say I’m autistic, people will understand and will talk directly and meaningfully to me, will not try to engage me in small talk, will not make assumptions about my behavior based on what they think I’m thinking, will not resort to stereotypes to define me. This would be a society that has normalized autism.

What are some of the most common (and/or enraging) stereotypes you encounter related to autism? Where/when do you feel free of these stereotypes?

I’m often told I’m combative and difficult. I’m told I’m pedantic, too specific, too literal, too direct, as if I can choose to speak some other way. People accuse me of faking my responses to things because I either “underreact” or “overreact.”

I’ve seen caregivers and parents infantilize nonverbal adult autists in the autists’ presence, by speaking about the autist as if the autist can’t hear them, and by talking to the autist as if the adult autist is a baby.

Neurotypicals have used babytalk on me.

I’ve heard caregivers and parents of autists dehumanize their children by referring to them as parrots when the autist is simply echolalic, and by saying that autists flap their hands, when the autist is simply stimming. I’ve heard parents and caregivers refer to meltdowns as tantrums, as if the autist chooses to have a meltdown, as if the autist is misbehaving.

Many people believe autism is a mental illness, and that if a person “doesn’t look autistic” they should “have a filter,” should “know better.”

I’ve heard self-hating autists attempt to separate themselves from the autism community by claiming they are “normal” because they are “high-functioning.”

I’ve heard people refer to autism as a social disease, but that doesn’t make sense, as viruses cause diseases within society, not autists. Autism is not a disease. Autists can’t stop being autistic. Autists generally keep to themselves, though autists also tend to value morality and are working as activists to heal society.

In your opinion, what are some well-written examples of stories (or writers) that include disabled characters in the right ways?

Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face, a memoir about the author’s childhood with cancer, is a book I’ve read countless times. Literary nonfiction has been my focus lately.

I’m currently reading Nobody, Nowhere, a memoir by Donna Williams, an autist. Williams’ book is maybe the first book I’ve read in which I see myself. The only other times I’ve felt seen was when I watched Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette and Douglass.

My beliefs about disabled characters transcend genre. I’m only interested in writers who show both how society treats disabled characters as well as how these characters see themselves. Disabled characters should not be othered in any way. I reject writing that frames the disabled person as either a hero, someone who is “brave,” or as a lesser human, someone the readers should pity.

Two novels I love that feature autistic characters, though the novels don’t say anything about autism are: Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Live in the Castle and Percival Everett’s Erasure—I read an interview recently in which Percival Everett states autism is the next evolutionary step. I hope this is so. The world would become an honest, safer, more logical place.

While the 2016 biographical film Christine isn’t a book, I believe the protagonist, Christine Chubbuck, is an autist. These autistic characters are rendered so realistically that I recognize their autism, recognize how misunderstood these autists are by the neurotypicals who believe there is something wrong with them.

Honest representation is vital, helps people discover themselves, though relatability is a luxury I see no point in pursuing.

Tell me about the project you are working on titled Unmasking.

Unmasking will be a collection of essays, cannibalized from older essays I’m revising as well as new ones. Writing is a form of communication, but writing is also a form of thinking, so I write to organize my thoughts, to know what I believe. I therefore struggled to write essays in the past, and eventually stopped writing them, stuck to fiction, because I had yet to accept my autism, had yet to know who I was, what I believed.

I no longer mask. Autists mask, but so do black people. Autists try to hide their “autistic” traits in the presence of neurotypicals while black people try to hide their “black” traits while in the presence of white people, though “autistic” and “black” traits are human traits.

I’m an autistic black person who has performed for neurotypicals of all races. I’ve performed for white people of all neurotypes, always in an effort to keep people comfortable, often in an effort to appear “normal.”

Always, I’d wake up the next morning with a social hangover, and would find myself vomiting into the toilet, whether or not I consumed alcohol the night before.

I’ve experienced autistic burnout as a result of performing socially. Autism is realness, is not-performing, so I will remain autistic, myself, at all times. I no longer drink alcohol, though I am still susceptible to social hangovers, so I avoid socializing, and I remain myself if I can’t avoid socializing.

Autism and race interest me not only as aspects of my identity, but also because race is a social construct, and a major aspect of (my) autism is that I don’t understand social constructs. They make no sense to me. I don’t accept them. Race interests me because I’m black, a loaded race in America, I’m also an autist, so I routinely break social norms, defying stereotypes.

Unmasking makes sense as a title for the collection of essays as I no longer want to hide myself. I accept myself.

Is there anything else you’d like to mention that I didn’t ask?

Neurotypicals and other non-autistic individuals, should never assume to know what autistic people are thinking based solely on our behavior—we can’t know this about anyone—and should understand that autists are honest people. Believe us when we discuss our experiences, no matter how “strange” we may seem to you.

Neurotypicals complain that I offend and confuse them, but they should understand that they offend and confuse me. Goes both ways. Please practice patience and kindness.